The open database for university spinouts

Help us empower university inventors to form spinouts from their research.

Spinout.fyi V2 database release

Published by Nathan Benaich on 19 June 2023.

Tl;drThe spinout product remains fundamentally broken, with dire satisfaction ratings, slow deal times, and excessive equity takes. The response from universities to scrutiny over the past year has been to ratchet up their lobbying efforts, rather than to improve the founder experience. It’s clear that this feudal system isn’t going to reform itself. With a new technological arms race raging, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Government needs to act now to encourage greater transparency, support alumni ecosystems, and consider implementing a uniform agreement to spinout with permissive terms. You can read more about our policy solutions here.

Momentum for change

In the year since we released the Spinout.fyi V1 database, the ground is beginning to shift. Spinouts - companies formed to commercialise inventions developed in universities - are moving from an at times obscure debate in the academic and venture worlds into a critical policy vector one towards technological sovereignty.

In the UK, we’ve seen the current government launch a review of the spinout landscape while the Labour Party’s Start Up Review adopted many of our policy proposals. Meanwhile, the German Government has taken an even bolder approach, using its control over universities to bypass their underperforming Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) via a planned national technology transfer agency. Universities of the Netherlands have adopted transparent principles for spinouts in an effort to harmonise deal terms across a dozen universities.

The Empire Strikes Back

But every action triggers an equal and opposite reaction. We’ve seen TTOs and their supporters begin to defend their model in earnest. This includes a report on TTO effectiveness from the University of Cambridge, a ‘rebuttal’ from UK Research and Innovation, and the Russell Group denouncing our recent op-ed in The Times. These responses have been characterised by:

- Swerving the real debate, by treating this as a single-issue dispute between founders and universities on the correct equity take rates, and simply ignoring the other challenges we discovered from our data.

- Dismissing founders’ experiences as anecdotal and continuing to point to the same set of benefits TTOs allegedly provide, even though many spinouts don’t enjoy them in practice.

- Setting the bar too low, and arguing that today’s disappointing results are the sign that the system is performing as well as it can.

These responses culminated in a rival set of proposals from an association of TTOs called TenU. Taking a Nasdaq penny stock and a business that took 33% dilution and 3% royalties as its case studies for success, the TenU guide essentially attempts to frame the current failed system as ‘best practice’.

Research from the University of Oxford itself has highlighted the impacts of the current system. It found that higher university equity stakes make start-ups less attractive to investors. It also found that only 5% of UK spin-outs raise over £25 million, which is a damning reflection on technology transfer, considering the quality of research in our universities.

As the now expanded Spinout.fyi V2 data below demonstrates, we aren’t talking about a handful of anecdotes, but a comprehensive system-level failure.

About the Spinout.fyi V2 dataset

The database now includes 205 unique entries (up 43% from V1) from 103 universities around the world (up 45% from V1). This continues to be the largest freely available global database of its kind.

At the time of their responses, 51% of spinouts had raised Seed rounds, 17% raised Series A rounds, and 2% raised Series B rounds. 15% were pre-funding and 3.5% no longer exist. 2.5% had exited by IPO and 8% exited via M&A.

Institutions covered include:

The spinout product continues to be a failure

TTOs have a dismal net promoter score of -52, up only 4 from last year. For context, that is significantly worse than most retail energy companies or high street banks.

TTOs often talk the talk about supporting founding teams, but founders often don’t realise these benefits in practice:

University of Freiburg: A lot of German TTOs just don't get it. They have no clue what it means to create value through start-up formation. They are killing the startups the moment they spin them out with the ridiculous terms they ask for. Crazy and a pity given the amazing innovation in the country.

UCL: The TTO didn't add any value in the project (no useful advice, no business insights, no business strategy,...). The TTO used the fact that very little information is available to founders about IP transfer, in order to squeeze them.

Slow deal-making sets spinouts up to fail

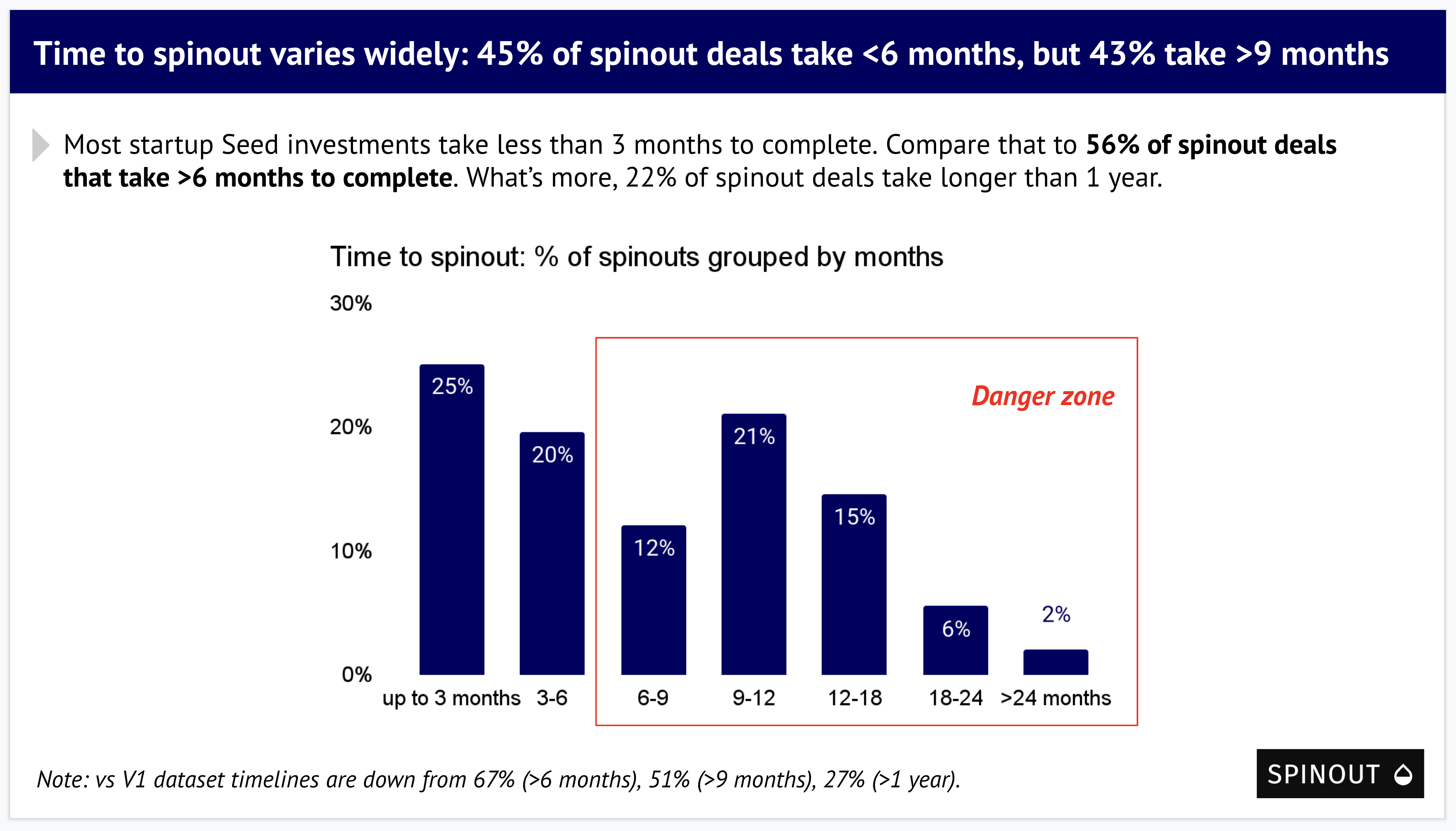

Most startups are able to raise capital in less than three months. In the US, it can take a matter of weeks to close a financing round. Strikingly, however, 56% of spinout deals take over 6 months to complete and 22% longer than a year.

When you’re starting a business in an emerging field, your pace of execution is crucial. Every month that funding and launch is delayed is a month another startup or large business can copy your breakthrough. TTOs generally underappreciate the importance of market execution over the original invention.

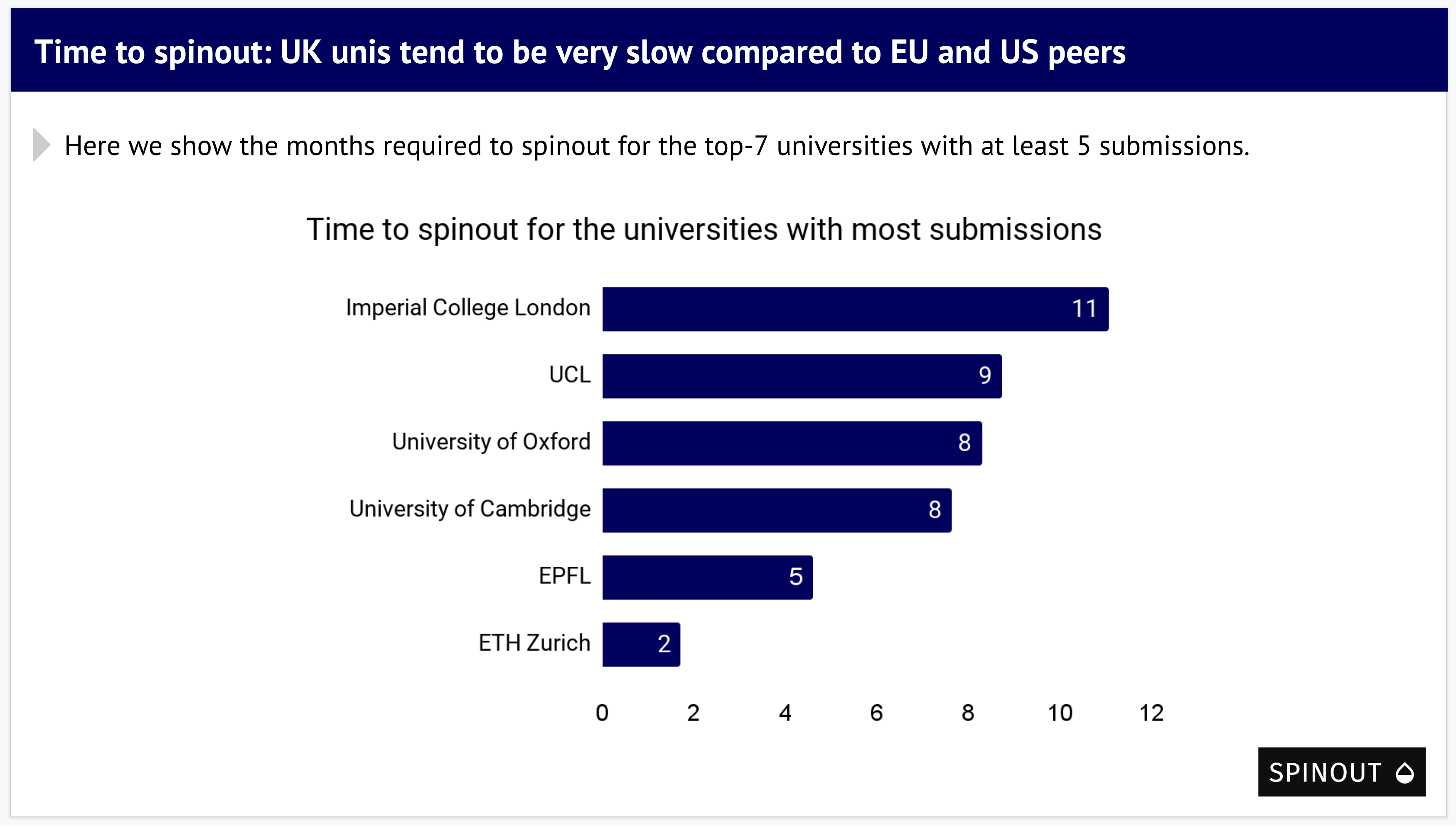

Launch times remain particularly slow at UK universities, which are noticeably slower than their US and European counterparts.

Here are some illustrative comments from founders who experienced this slowness:

University of Copenhagen: As always, it the slowness that kills.

Stellenbosh University: Our experience was generally pretty unsatisfactory. The university is a bureaucratic beast that does not operate at startup speeds. Furthermore, they do not provide much industry specific support, despite the industry growing exponentially.

This poor service ain’t cheap

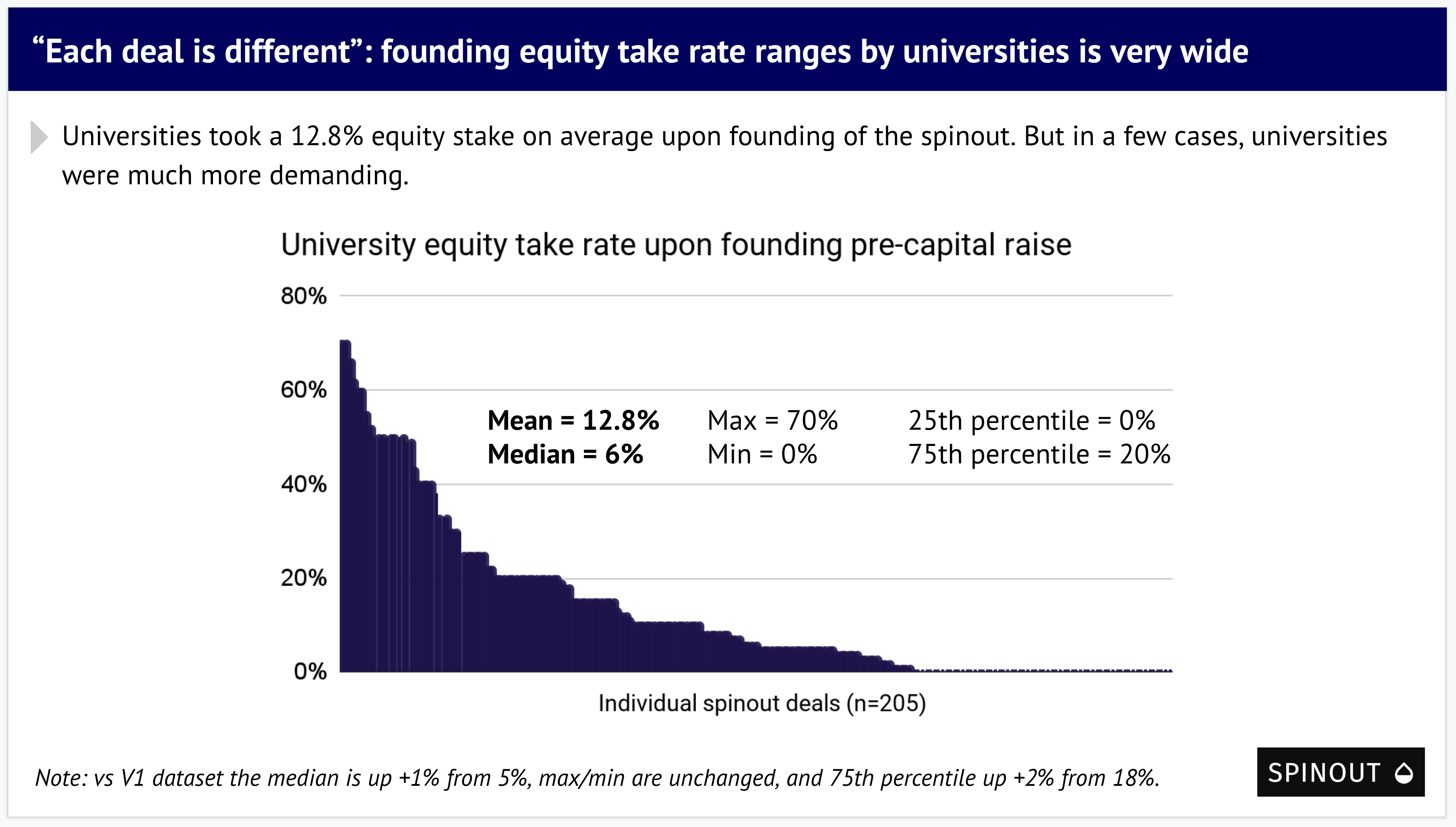

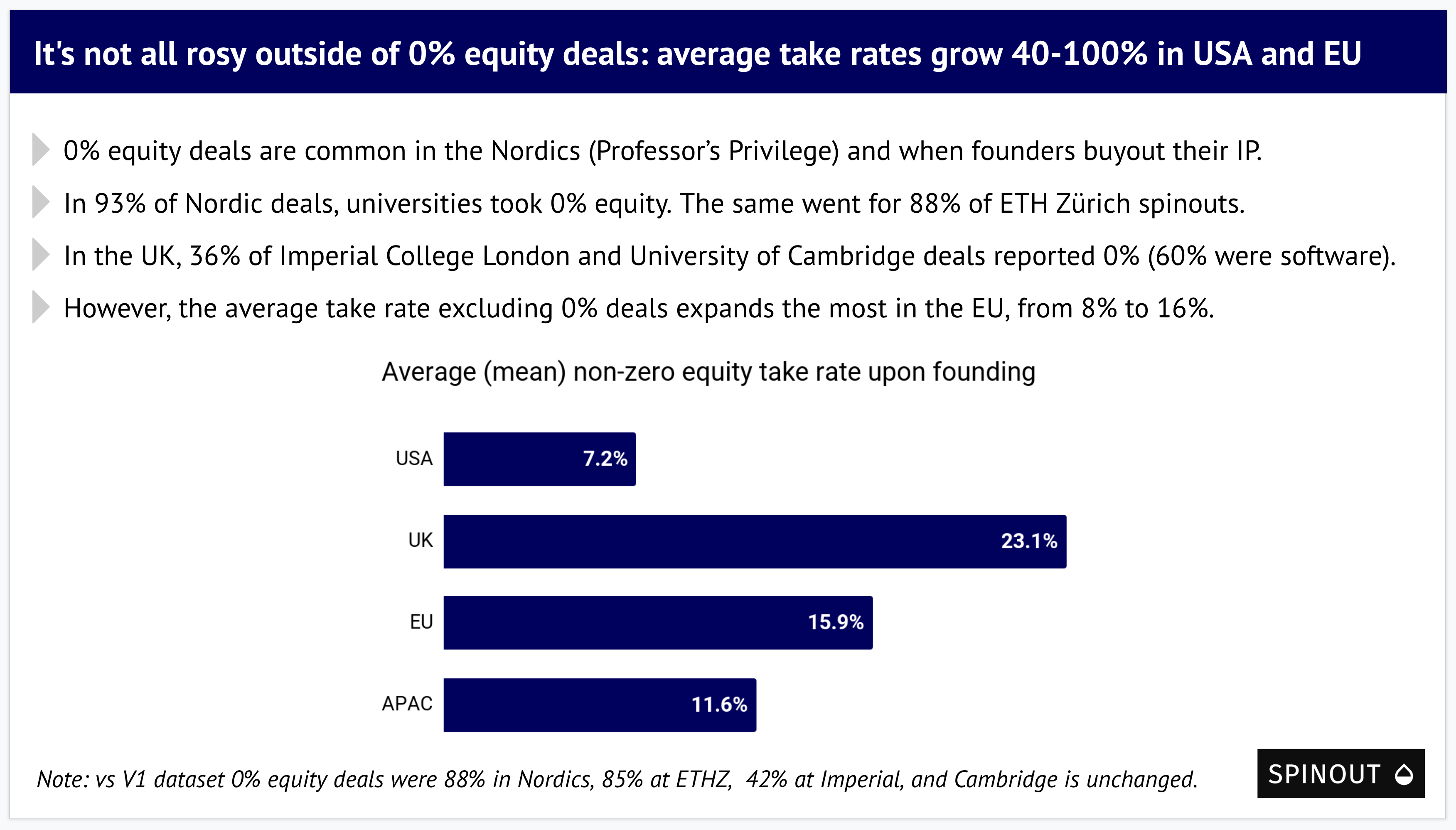

Despite TTOs’ fightback centering on equity take rates, the average equity take across the Spinout.fyi V2 dataset remains almost unchanged at 13%. This figure is incredibly high for a passive shareholder that has not taken on any risk. While universities should be compensated for the time or facilities they have provided, European TTOs approach the spinout process as a shakedown rather than the start of a long-term partnership. As well as being unfair on founders, this is deeply off-putting for private venture capital. That’s why, of the £24 billion raised by British technology companies in 2022, less than 5% of this capital was invested into businesses that emerged from our universities. Too often, TTOs choose a larger stake of a small business that they’ve set up to fail, rather than a smaller stake in a potential multi-billion dollar success story.

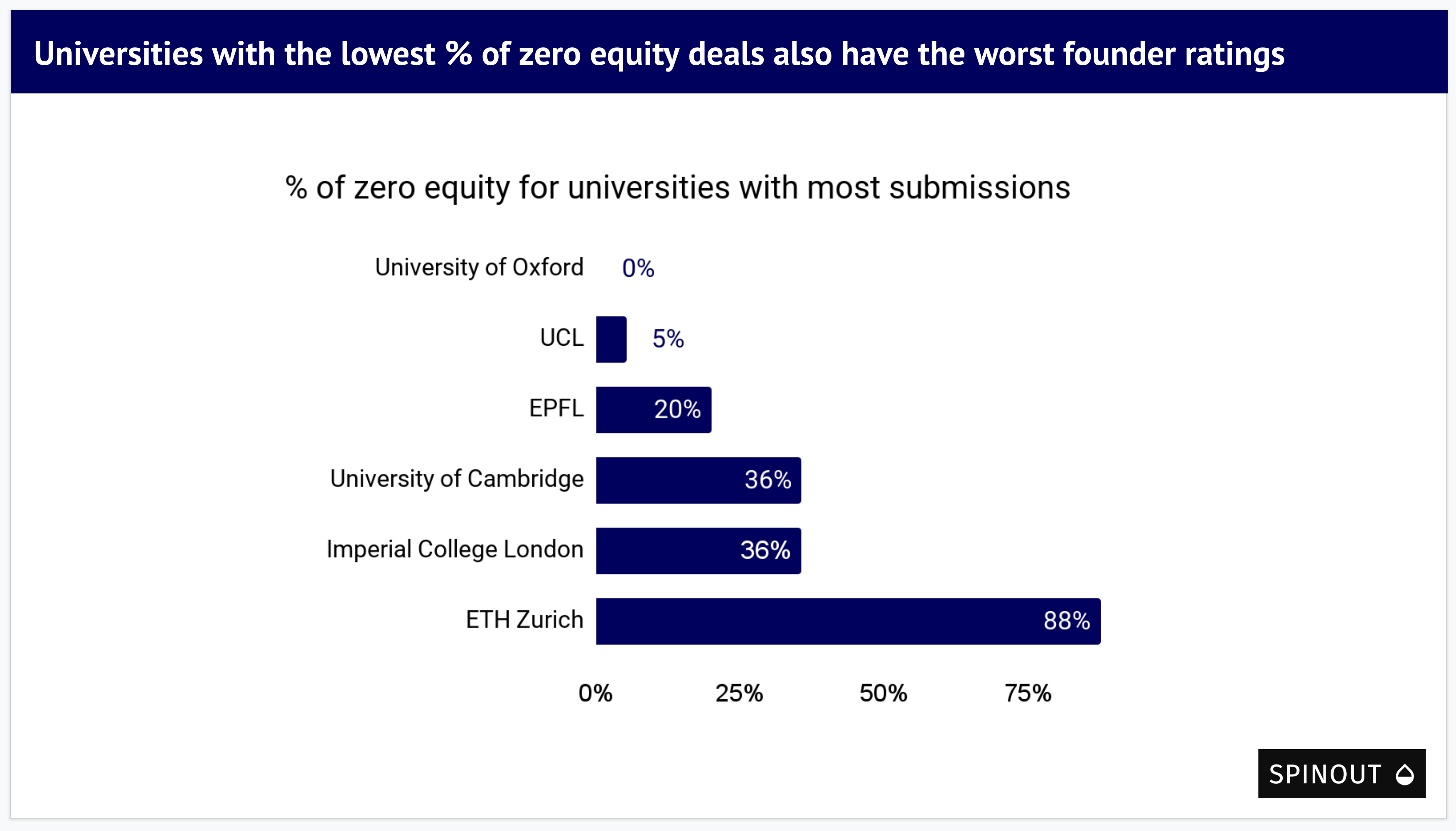

There are, however, some examples of good practice. For example, the Professor’s Privilege system in the Nordics means that 93% of their deals saw the university take 0% equity. Similarly, the University of Waterloo ascribes all IP ownership to its inventors who may then choose to use the TTO to file their IP or do it themselves. Encouragingly, a significant minority of Imperial College London and the University of Cambridge’s deals are 0% equity.

However, the overall picture continues to show UK universities being particularly demanding in terms of equity, requiring 2.5x the share taken by EU universities on average, and 4x that of US universities.

These equity take rates are particularly egregious when it transpires that a third of spinouts eventually develop to the stage when they no longer rely on their founding IP. Again, market execution >> original invention.

Royalties and continued board control

Our data shows that spinout founders often see their former institutions continue to claw back revenue via royalties or exert control over their day-to-day operations.

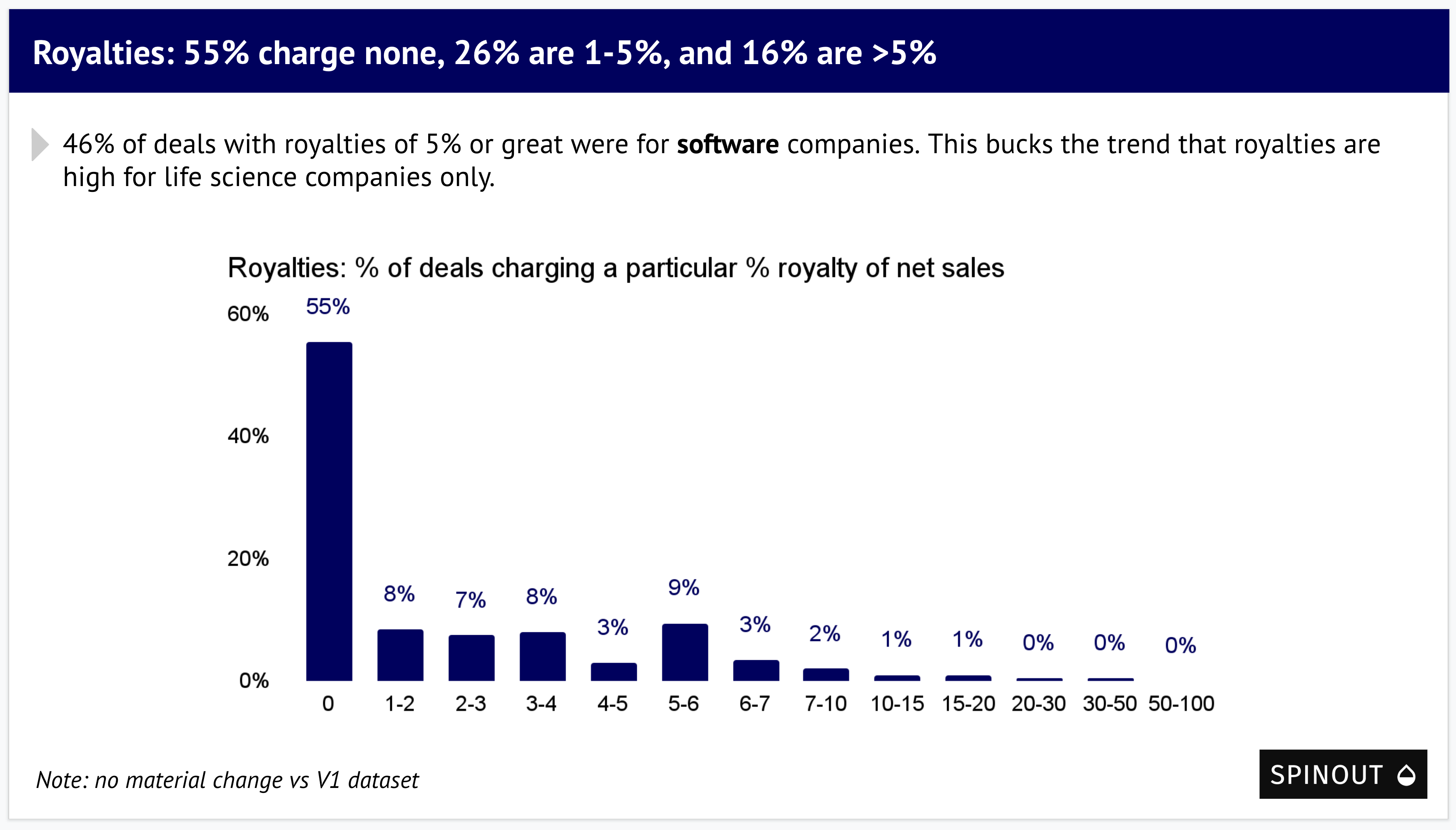

Indeed, 45% of deals had royalties attached, with 16% set at over 5%. In the past, universities have defended 5%+ royalties on the grounds that they should be compensated for life-changing pharmaceutical breakthroughs developed in their labs. However, almost half of these 5%+ royalty deals were for software companies.

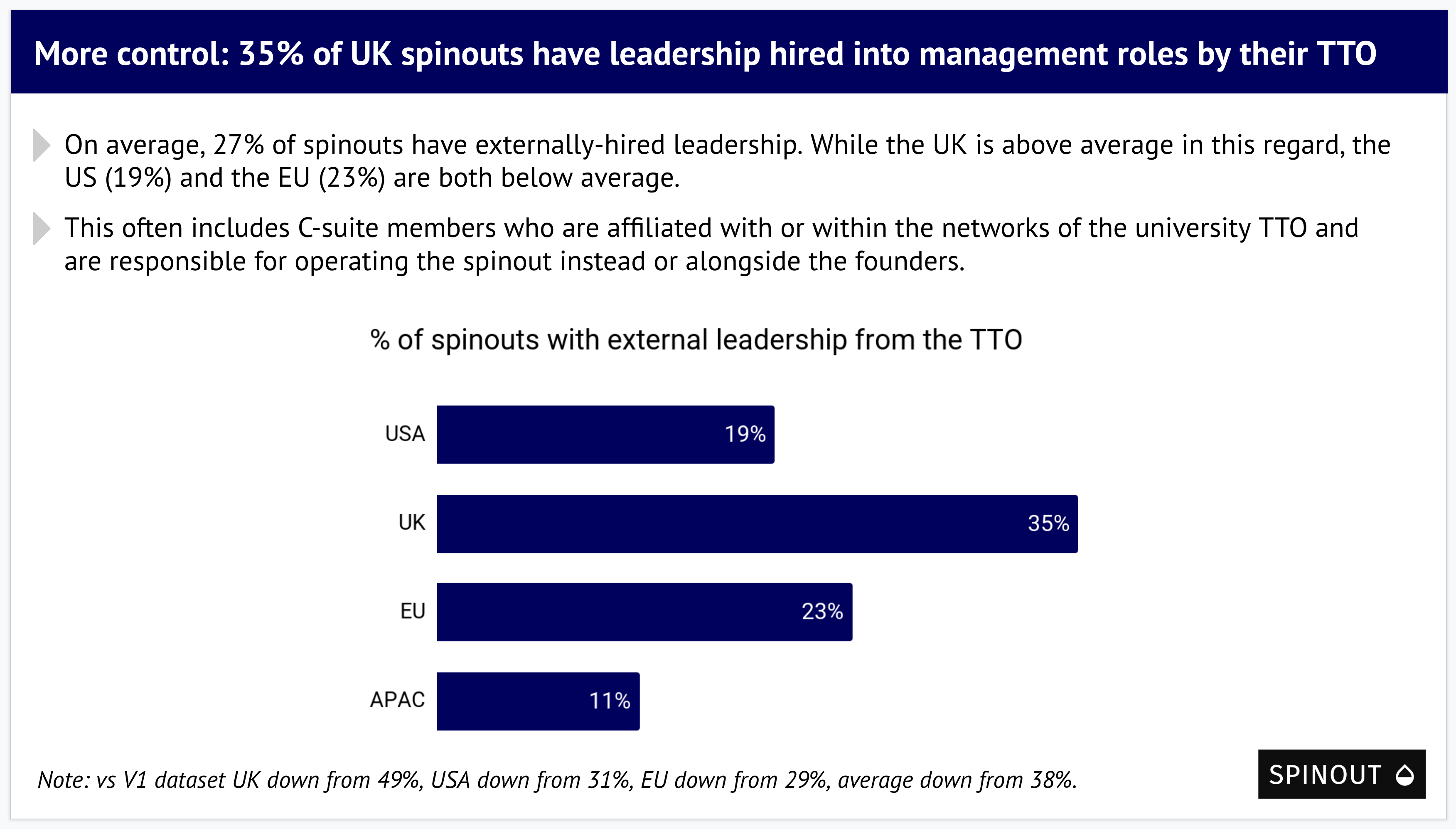

Beyond levying royalties, 27% of spinouts see external leadership hired in by the TTO, with the figure rising to 35% for UK spinouts. This often includes C-suite members who are affiliated with the TTO and whose interests are primarily aligned with the university rather than the founder’s vision. We note that this approach is at odds with the fact that universities and TTOs are not “professional investors”.

No wonder alumni ecosystems are so weak

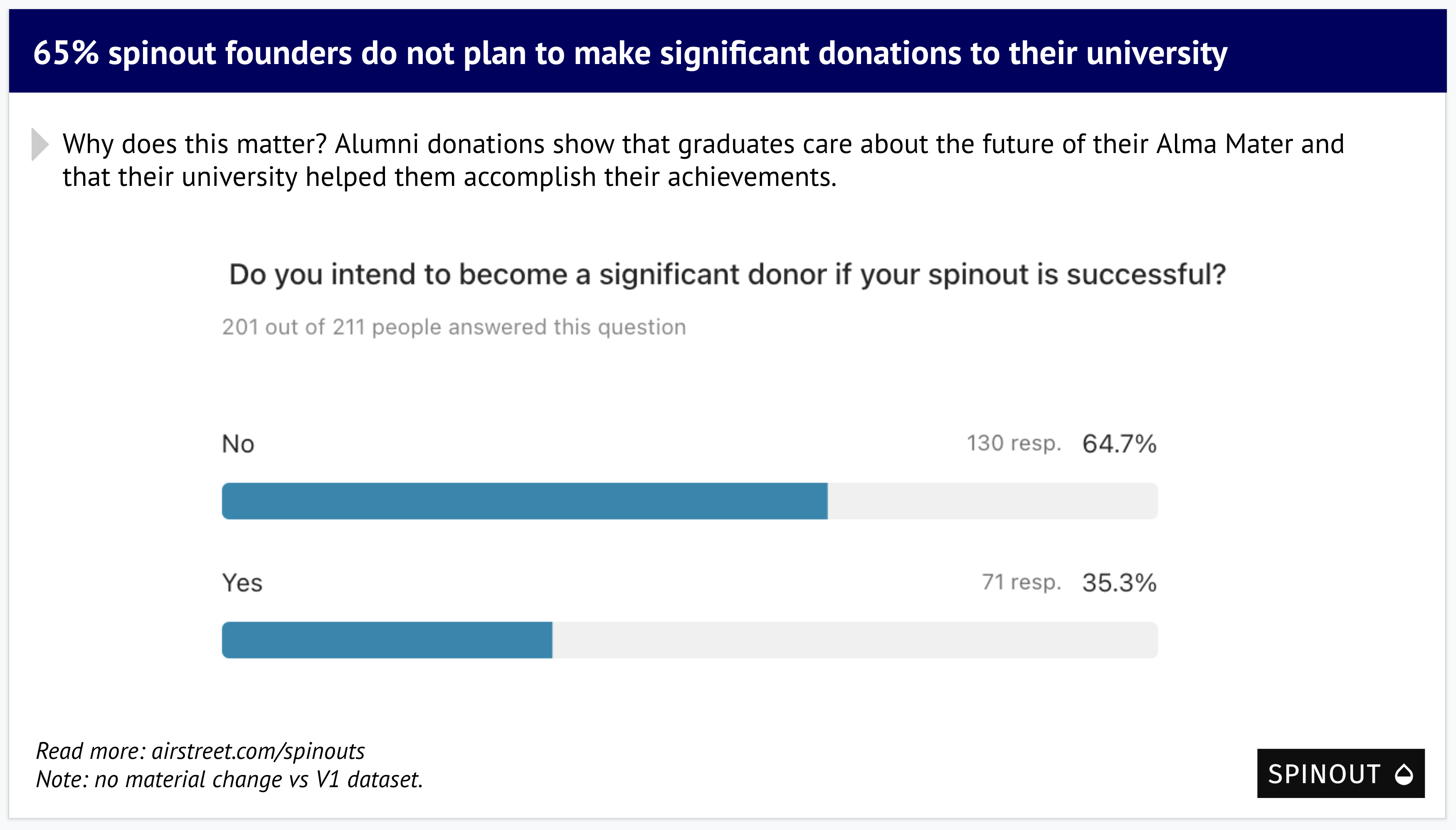

Ecosystems of founders supporting other founders are critical to create and sustain thriving startup clusters. For this to happen, spinout founders must be happy with their experience and be willing to give back to their ecosystems through investing, donations, mentorship and more.

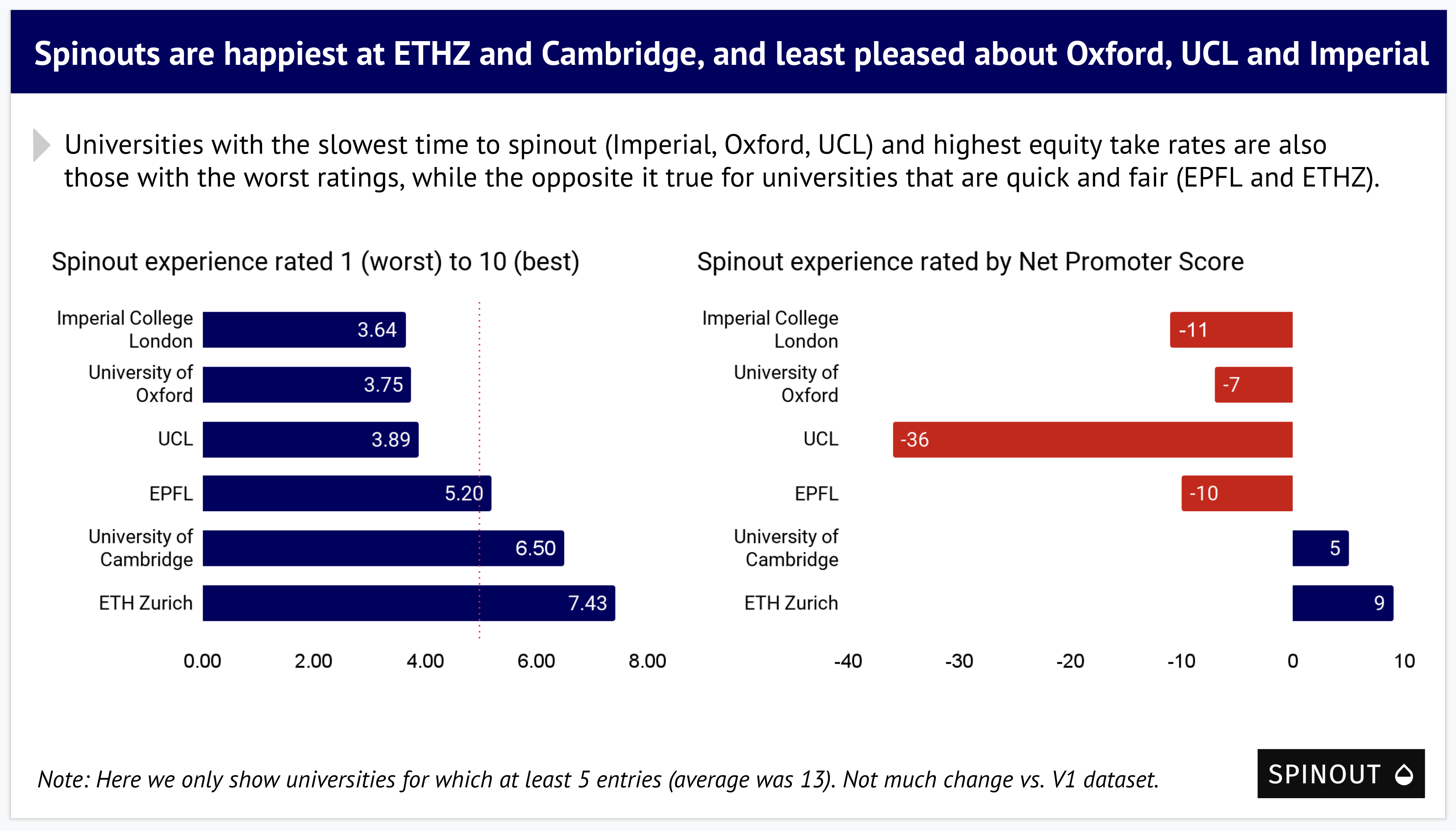

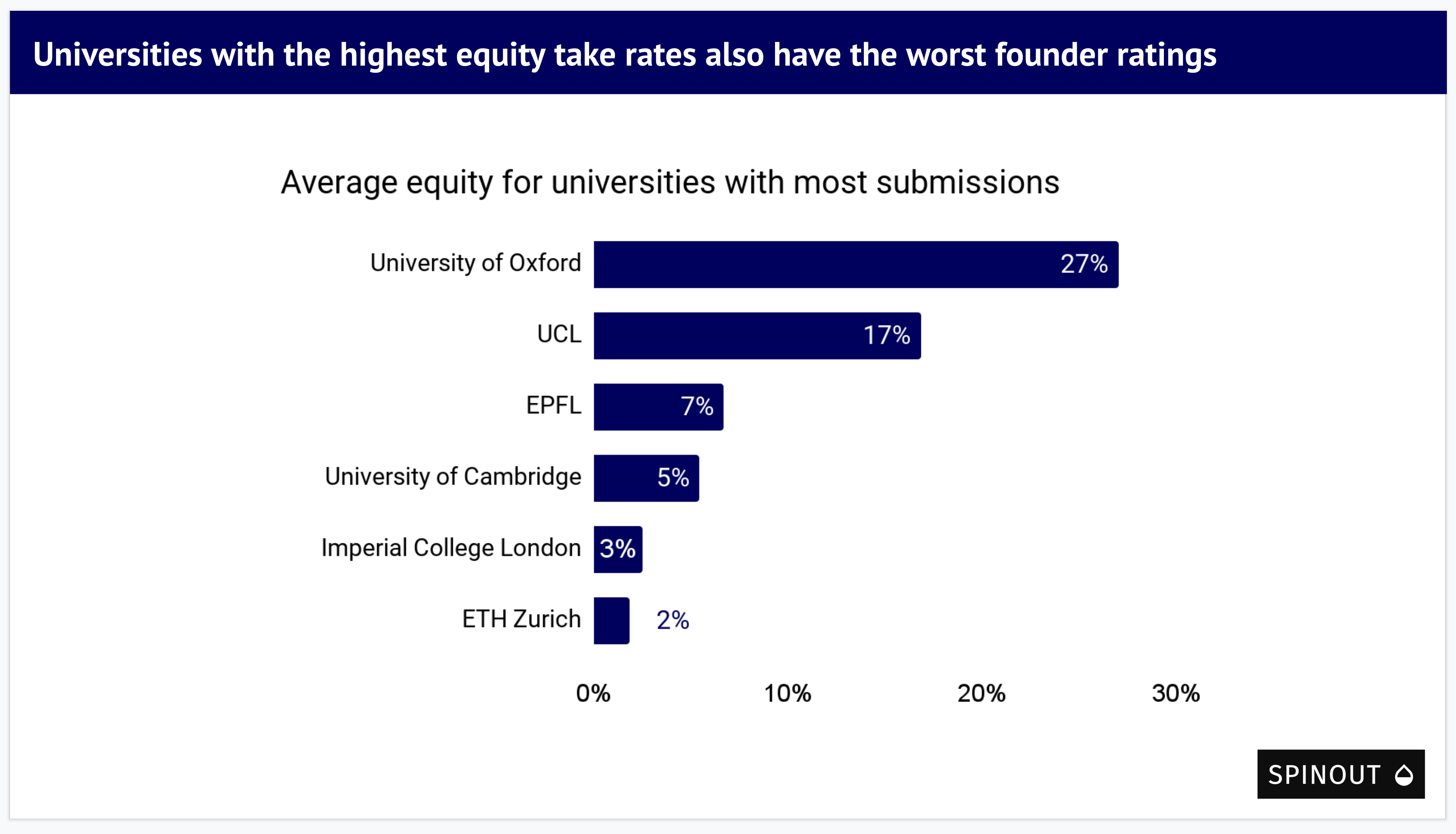

However, our data shows that there is a clear relationship between a) slow times to spinout, b) high equity take rates and c) a TTO receiving a poor NPS score from its founders.

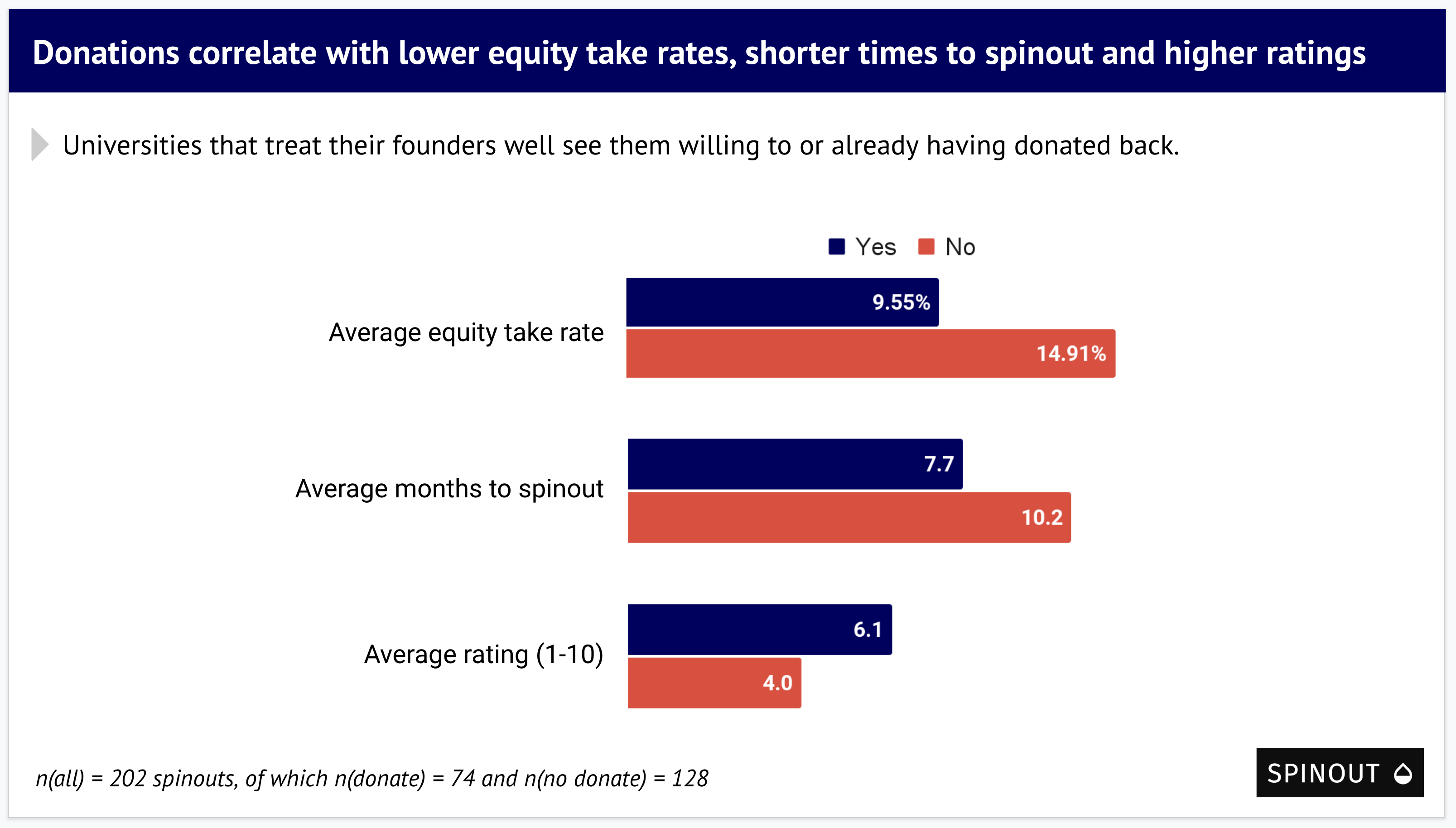

Based on this, it’s no surprise that almost two-thirds of spinout founders do not plan to make significant donations to the institutions that were allegedly essential to their success. This makes sense: why would an unsatisfied customer support their service provider?

To this more clear, our data shows that founders who have or are planning on making significant donations to their alma matter have on average parted ways with 57% less equity, spent 25% fewer months negotiating, and rated their spinout experience 53% better than founders who will not donate. Tl;dr if founders get a more permissive spinout deal, they are more likely to donate.

What works in Stockholm or Stanford can work in London or Freiburg

One consistent theme throughout the survey was the sharp disparity between regions. While nowhere has an unblemished record, we consistently see better scores across time to spinout, equity take rates, and overall satisfaction in the US, the Nordics and Switzerland. This demonstrates just how unambitious and, frankly, wrong the TTOs are when they say the system has no real scope for improvement…

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: The University has been helpful post spinout, with advisors and premises.

Uppsala University: The university has helped us post spinout with access to labs and equipment, helping us employ industrial PhD's, collaborating on research, etc.

Cornell University: Our company agreement with Cornell is for 4% dilutable equity and 0.5% royalties of net sales for any products derived using the original founding IP with Cornell. The company also currently retains the intellectual property and not the university.

Setting a national policy isn’t intervening in a market - it is creating one

A broken spinouts system isn’t just a problem for a small group of entrepreneurs. It’s a problem for all of us. Technology is becoming the primary frontier for a new era of geopolitical competition. China is pumping seemingly unlimited amounts of money into its tech sector, while the US continues to act as a magnet for the best talent. Europe needs to decide if it wants to be a leader or a bit-player.

With some of the best engineering and computer science departments in the world, we strongly believe that European dynamism is just waiting to be unleashed.

Government can do some of the work here: through targeted support or the smart use of procurement, but it can never act as a viable alternative to a thriving early stage venture ecosystem.

The lack of change since V1 shows that many TTOs do not believe that there is any merit in founders’ stories. TTOs take the view that founders should be grateful for any deal on the terms they dictate.

This is encapsulated in the story of Bo Jing who founded Oxford Nanoimaging on the basis of his PhD work at the University of Oxford. At founding, he was left owning only 25% of his own business and forced to pay 3.5-6% sliding royalties on ONI’s net sales. When Bo protested this years later, the University took him to court in the UK.

Bo won some important new consumer rights protections for PhD students, but he ultimately lost the case because the judge did not take issue with his spinout deal putting him and his business at a disadvantage by being unfair. ONI was forced to pay £700,000 in backdated royalties. The judge suggested that Bo should never have taken the deal and instead opted for the “nuclear option” of refusing to sign the documents until the university offered him a better deal. This is madness. Spinout founders should categorically not have to invoke a “nuclear option” to get a fairer deal.

This is the bind that founders find themselves in today. This is a situation where a university holds all of the bargaining power - there is no ‘nuclear option’. Founders have a binary choice between agreeing to all of their demands or never starting their spinout. The result is that we're likely to have induced the formation of more successful "sneakouts" - spinouts that stealthily escape the system entirely - than official spinouts. This feudal system has no place in any advanced economy, especially in a region that prides itself on its science and tech leadership. When a broken system fails to reform itself, the government needs to step in. We would encourage policymakers to consider our recommended policy solutions.

Help us rewrite the spinout playbook

Founders often lack information to negotiate their spinout deals. They end up with unfair deal terms and an unnecessarily awful spinout experience.

Founders, help us give future founders a leg up in the process by submitting your anonymous deal terms at https://www.spinout.fyi.

To download the slides in this blog post, click here.